Perspectives on Mechanical Small Bowel Obstruction in Adults_Juniper Publishers

Authored by Elroy Patrick Weledji

Abstract

Small bowel obstruction is a serious and costly

medical condition indicating often emergency surgery. Delay in operative

intervention may lead to an unnecessary bowel resection, an increased

risk of perforation and an overall worsening of patient morbidity and

mortality. A thorough history and examination would distinguish simple

from strangulation obstruction and facilitate appropriate management.

The article reviewed small bowel obstruction and emphasized the

importance of history taking and examination in the early diagnosis of

its cause, thus, facilitating appropriate management.

Keywords: Small bowel; Obstruction; Mechanical; Clinical features; TreatmentIntroduction

Small bowel obstruction accounts for about 85% of

cases of intestinal colic and the other 15% are due to large bowel

obstruction [1].

It is a serious and costly medical condition constituting 1.9% of all

hospital and 3.5% of all emergency treatment that has led to laparotomy

in the United States [2-4].

The main clinical issue is to determine whether the obstruction affects

the small bowel or the colon, since the causes and treatments are

different. Delay in operative intervention may lead to an unnecessary

bowel resection, an increased risk of perforation and an overall

worsening of patient morbidity and mortality. The overall mortality is

approximately 10% and is greatest in patients with ischaemic bowel which

may or may not have perforated prior to surgery [2,5,6]. The most common causes of death are intra-abdominal sepsis, myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism [1-6].

Intestinal obstruction may be mechanical which presents with colicky

pain or paralytic which is painless being aperistaltic. The latter is

commonly seen in postoperative ileus which resolves after 24-48 hrs or

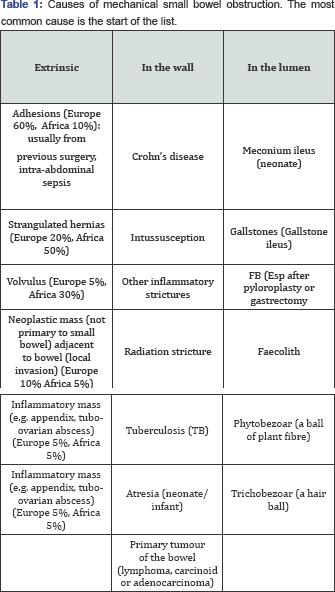

from electrolyte (potassium) imbalance with diuretic use [6,7]. Mechanical obstruction may be due to obstruction in the wall, in the lumen or outside the wall of the bowel (Table 1) [2].

There is a degree of overlap as mechanical obstruction can progress to

paralytic obstruction (ileus) as it becomes more severe. Small bowel

obstruction may be simple obstruction that can wait for 24hrs or

strangulating obstruction (closed-loop) where there is interruption of

the blood supply of the bowel requiring an immediate operation [2,6-10].

Discussion

The visceral pain of intestinal colic is from

increased peristalsis against the obstructive lesion is usually referred

towards the midline rather than being localised as the gut has a

midline origin of development. The visceral sensory fibres are cARGHied

by the sympathetic nerves on their way to the spinal cord. The

consequences of bowel obstruction are progressive dehydration,

electrolyte imbalance and systemic toxicity due to migration of toxins

and bacteria translocation either through the intact but ischaemic bowel

or through a perforation [2,5].

Aetiology of Small bowel obstruction

There are several possible causes and the

epidemiology varies considerably from region to region. Adhesions is the

cause in 80% of instances. They are usually from previous abdominal

surgery and the use of abdominal mopping gauze swabs or towels [11-15], but may also arise from previous intraabdominal sepsis [11,12,14].

They produce kinking of the bowel or obstruction from pressure of a

band or volvulus. Intestinal adhesions are the commonest cause of

mechanical small bowel obstruction in the western world due to the

greater number of operations performed [2,11].

Intestinal adhesions to other vascular structures occur as injured

peritoneal cavity need to gain some extra blood supply during the

healing process [12-14].

Thus by minimizing disruption of the peritoneal cavity

minimially-invasive surgery can help reduce the probability of adhesion

formation [15].

Inguinal hernias are the commonest cause of mechanical small bowel

obstruction in the developing world where the uptake of modern medicine

is low with the consequent delay in surgical interventions [16].

Usually pressure of the neck of the sac causes obstruction especially

with the nARGHow femoral and indirect inguinal hernia defects and

occasionally internal hernia, and, it may be associated with

strangulation. Primary small bowel volvulus is a life-threatening

surgical emergency requiring immediate laparotomy following

resuscitation. It occurs in the 'virgin' abdomen with no anatomic

abnormalities nor predisposing factors. It is often seen in Africa and

Asia, and seems to be associated with special dietary habits (high fibre

diet) especially after a fast causing the incipient weight of the

terminal ileum to rotate round the short base of the mesentery. The main

problem is to differentiate it from other causes of obstruction that

can be treated conservatively Central abdominal pain resistant to

narcotic analgesia should heighten the suspicion of the diagnosis [17].

Rarer causes of small bowel obstruction are neoplasms (usually

metastastic and thus extrinsic) as primary small bowel malignancy is

rare. Intussusception in adults is rare and always require a laparotomy

as it is commonly due to an underlying malignancy such as lymphoma or

carcinoma. Any inflammatory mass such as diverticular, appendiceal,

tubo-ovarian ileo-caecalCrohn'setc, may cause small bowel obstruction by

blocking the ileocaecal valve or by causing a localized ileus [18,19].

The nARGHowest part of the small bowel is the terminal ileum which is

the preferred site of obstruction by most of the luminal causes. A right

iliac fossa mass in a patient with iron- deficiency anaemia from an

occult chronic bleeding is caecal carcinoma or other malignancy until

proven otherwise. These patients require computer tomography (CT)

scanning±colonoscopy for further elucidation [2,19].

Luminal obstruction from gallstone (gallstone ileus), hair

(trichobezoar), vegetable matter (phytobezoar) or foreign objects are

rare [19].

The rare patient with a Richter's hernia in which only the

antimesenteric portion of the small bowel is trapped without bowel

obstruction may be undetected on physical examination, and, patients

with partial obstruction can be considered at minimal risk of

strangulation. Rarely small bowel obstruction can be caused by internal

hernias related to mesenteric defects or recesses [9].

A modern clinical example is the internal hernias that develop after a

laparoscopic gastric bypass in which small mesenteric defects

(transversemesocolon, enteroenterotomy or behind the Roux limb can be

created and there are fewer adhesions to tether small bowel loops and

prevent them from herniating causing obstruction and potentially

strangulation. In addition patients who have greater degrees of weight

loss after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass may be more prone to

internal hernia because of loss of the protective space-occupying effect

of mesenteric fat [10].

How to tell the aetiology, level and severity of obstruction preoperatively?

The four cardinal clinical features of intestinal

obstruction are colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation and

abdominal distension. The history, examination and investigation will

help tell the aetiology, level and severity of the obstruction. These

have considerable bearing on the indications for operation, and on the

necessary preoperative preparation.

History: The onset of the obstructive symptoms

is usually sudden with high small bowel obstruction but more gradual

with low small bowel obstruction. The colicky pain comes with greater

frequency in high small bowel obstruction, about every 5 minutes in

jejunal obstruction, but every 30minutes in ileal and colonic

obstruction. The pain is typically central in small bowel obstruction

but where strangulation of the bowel has occurred the pain may become

constant and localised. If the colic is in the lower abdomen it is more

likely to be due to colon obstruction. Vomiting follows the pain and for

high obstructions vomiting is more profuse and occurs earlier.

Initially food contents are vomited but later the vomit becomes

faeculent (brown and foul smelling) [1,2,19]. The 24 hour secretory function of the proximal gut is illustrated in Table 2. It gives an indication of the amount of fluid that can be sequestered in the intestines or lost in the vomitus [2,6].

The clinical history may establish other features indicative of the

likely aetiology of the obstruction. A history of abdominal surgery may

suggest adhesive small bowel obstruction. A past history of colorectal

or other intra-abdominal malignancy, recent alteration in bowel habit or

the passage of blood is suggestive of neoplasm.

Examination: The examination findings will

depend on the stage at which the patient presents. The patient with

complete obstruction (no passage of flatus and faeces) are at

substantial risk of strangulation (20-40%) but a patient with chronic

obstruction may appear generally quite well with normal vital signs [20].

On the other hand the patient who has an acute closed- loop small bowel

obstruction may be profoundly ill, toxic, tachycardic, pyrexic and may

have a leucocytosis at the time of presentation [21].

A tense, tender, irreducible lump with no cough impulse especially over

a hernia orifice with often erythema of the skin is strangulation until

proven otherwise. Occasionally, the hernia is internal and not palpable

[20,21].

The physical findings would include dehydration, abdominal distension

and sometimes visible peristalsis. Dehydration assessed by examination

of the mucous membranes and skin turgor is an indication of severe fluid

depletion which is more marked in high than low small bowel

obstruction. Abdominal distension is usually evident and more marked the

more distal the obstruction, but it is more an indication of the site

than the extent of obstruction. Swallowed air, gas from bacterial

fermentation and nitrogen diffusion from the congested mucosa are all

responsible for the increased intestinal gas [5,6].

The abdominal distension is minimal in high small bowel obstruction and

more prominent in low. In low small bowel obstruction distension is

mainly central. In colonic obstruction distension is mainly in the

flanks and upper abdomen. Abdominal distension may be so marked as to

render further assessment of the intraabdominal contents impossible. The

cause of the obstruction may be evident (e.g. scars from previous

surgery, a tender irreducible hernia, an abdominal mass e.g.

intussuception or carcinoma of bowel) [5,6,12].

Rarely a mass be felt, or an irregular enlarged liver may suggest a

malignant lesion as the cause of obstruction.Percussion produces a

tympanic note and auscultation high- pitched tinkling, long-lasting

bowel sounds. If the obstruction is advanced there may be signs of bowel

strangulation (worsening constant pain, toxic patient, tachycardia,

hypotension and pyrexia) with reduced or absent bowel sounds (paralytic

ileus) [1,6].

It may be clinically difficult to distinguish with any certainty

between simple obstruction and strangulation but the later condition is

obviously very serious if overlooked [6,20].

Simple obstruction presents with colicky (visceral) pain but no pain

(somatic) on coughing as sign of peritonism. However, there is mild

generalized abdominal tenderness from the distension with gas and fluid.

Strangulation (closed-loop) obstruction usually has an acute onset of

severe pain which is constant and associated with cough peritonism [21].

Digital rectal examination is mandatory in intestinal obstruction

although rectal cancer is a rare cause of intestinal (large bowel)

obstruction unless very advanced. Assessment of the cardiovascular and

respiratory systems is necessary in small bowel obstruction as most of

these patients will require surgery [6].

Treatment of small bowel obstruction

In the past 15 years, there have only been some modest progress and advancement in the treatment of small bowel obstruction [2,4,6].

It has been demonstrated convincingly by the NCEPOD (National

Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths) that patients with

intestinal obstruction who are hypovolaemic have a higher morbidity and

mortality if not adequately resuscitated prior to surgery [22].

This is exacerbated by the vasodilation of anaesthesia which may cause

catastrophic hypotension and renal failure. Treatment commences with

resuscitation by correcting fluid and electrolyte deficits, nasogastric

tube decompression and analgesia. There is careful monitoring with fluid

balance charts, pulse and blood pressure as resuscitation is continued

until the central venous pressure is restored and a consistent adequate

urinary output of atleast 30mls/hr for an average 70kg patient [2,6,23]. The management of simple obstruction may be either operation or observation depending on the likely cause [24].

If simple obstruction is thought to be due to adhesions conservative

treatment is initially indicated as spontaneous resolution will occur in

up to 70% of patients with obstruction secondary to adhesion [2,6].

Surgical intervention is necessary when conservative treatment with

nasogastric decompression and intravenous fluid resuscitation fails

after 48hrs as the patient should not remain obstructed for more than

that length of time, or with evidence of peritonitis from strangulation

obstruction [2,24,25]. Conservative treatment often succeeds in postoperative obstruction from adhesions or ileus [25]. Conservative treatment may be appropriate for inoperable carcinomatosisperitonei.

Operation is indicated for

a) Strangulation obstruction as soon as patient is

rendered fit. The overall operative mortality for strangulated hernia is

10% and so adequate preoperative resuscitation is crucial [2,22-24,26];

b) Obstruction due to some cause that will not

settle e.g. obstructed hernia, carcinoma, gallstone ileus etc. In the

latter, the obstructing gallstone is removed either by expression or by

the use of stone-holding forceps via a proximal transverse enterotomy

which is repaired by two layers of suture. The chronic

cholecystoduodenal fistula is left undisturbed [2,6].

c) Simple obstruction that fails to settle on

conservative treatment. The presence of fever and leucocytosis should

prompt inclusion of antibiotics in the initial treatment regimen. After

relieving the cause of the obstruction by operative intervention, it is

usually necessary to decompress the stomach and the greater part of the

small bowel by nasogastric drainage. Intestinal peristalsis is inhibited

by gastric distension, and is restored when this is relieved.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is usually necessary if obstructed intestine has

been opened [2,6,26,27].

Conclusion

Small bowel obstruction remains a common and

difficult problem encountered by the abdominal surgeon. Following

resuscitation a precise history may indicate the pathology and physical

examination supported by basic imaging may indicate where the pathology

is. These have considerable bearing on the indications, timing of

intervention, and necessary preparation should operation be considered.

Appreciation of fluid balance, acid-base-electrolyte disturbance and the

importance of preoperative resuscitation decrease the morbidity and

mortality from intestinal obstruction. Advances in minimally- invasive

surgery would help minimize adhesion formation, the commonest cause of

intestinal obstruction.

To Know More About Advanced Research in Gastroenterology &

Hepatology Journal

click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/argh/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/argh/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment