Updating on Neuroendocrine Tumors New Clinical Evidence in the Search of the Ideal Treatment Sequence_Juniper Publishers

Authored by

Juan Manuel O'Connor

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) represent a

heterogeneous clinical entity with an increasing incidence as shown by

the different registers available. As opposed to other solid tumors,

NETs represent a challenge, not only from the diagnostic standpoint but

also in terms of treatment strategies. According to the data published

by our Working group, ARGENTUM GROUP [1], with more than 600 patients assessed, roughly 60% of the cases present with metastatic disease from the onset.

The reason why the incidence of advanced disease is

high since early onset may be due to a bias, for most of the physicians

in our Group are oncologists. Moreover, about 20% of the patients

included present poorly differentiated NETs, a heterogeneous subgroup,

with high risk and poor outcome according to the different series

reported.

G grading, in the classification of neuroendocrine

tumors has been proposed by ENETs to identify three categories according

to the proliferative value, Ki 67: Ki 67 under2 %, G1; Ki 67 between 3

and 20%, G2; and wth a Ki 67 over 20%, G3.

Although for therapeutic reasons patients with well

differentiated tumors were classified in the same manner, at present the

cut off point for G3 has been modified. As reported by Sorbye et al. [2]

55% is the parameter to better discriminate this group of patients,

based on a retrospective series including more than 300 patients with

poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Moreover, the same study

showed that Ki 67 was a predictive factor of response for platinum-based

chemotherapy.

As recently reported and commented by Dr. G. Rindi at

the 2016 Annual ENETs Conference a different biological behavior has

been described even for the so called NEC G3 tumors, that is, poorly

differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas; a sub classification has been

proposed for NET G3 to better differentiate them from the real NEC G3,

considering that the former present more favorable characteristics for a

good outcome, and even the potential somatostatin receptor expression

in some cases. This sub classification is important because it favors

new treatment options at least in some G3 subgroups, although a

retrospective validation is required for better staging.

In a retrospective series including 136 patients with G2 gastroenteropancreatic tumors, Milione et al, [3]

the Italian group, showed a possible staging system based on

morphological, proliferation features, defects in the mismatch repair

system (dMMR) , CD117 expression and site of origin.

The multivariate analysis in that study showed that

the factors mentioned above were independent in NEC G. Three prognostic

categories were defined based on these factors in G3, a category

including well differentiated tumors vs poorly differentiated tumors and

Ki 67, <55% versus >55%, with a 43.6 month survival in patients

with well differentiated tumors and Ki 67 between 20 and 55%.

In the case of poorly differentiated tumors and Ki 67

ranging between 20 and 55%, median survival was 24.5 months, and

finally the group with the poorest prognosis, poorly differentiated

tumors with a Ki 67 over 55%, with a survival of 5.3 months. This study

clearly shows an active area for clinical research in this subgroup of

patients with limited treatment options at present.

New clinical evidence, randomized studies

At the Annual Meeting of the European Conference held

in Vienna in 2015 the results of different clinical trials in

neuroendocrine tumors were presented. All of them were randomized

comparative studies, evaluating efficacy and tolerance of different

treatment options. Although already available in the field of

neuroendocrine tumors the confirmation of a well designed comparative

clinical trial to show the advantages in terms of survival is still

pending.

The RADIANT4 [4]

study included 302 patients and compared the use of everolimus, (10mg

/day) vs placebo in patients with a diagnosis of Grade 1, 2 advanced,

progressive, well-differentiated, non-functional neuroendocrine tumors

of lung or gastrointestinal origin.

The primary endpoint, progression free survival (PFS)

was achieved; everolimus demonstrated a 52% reduction of progression vs

the non-active treatment arm, which translated intomPFS of 11 months vs

3.9 months in favor of everolimus, which was statistically significant.

The most significant fact in the study is the inclusion of

neuroendocrine tumors of bronchial- lung origin, where the role of m-TOR

inhibitors was not clear.

TheNETTER-1trial compared the use of Lu 177 DOTATATE,

(Lutathera) plus Octreotide (30mg) in patients with NETs of

gastrointestinal origin and advanced disease versus Octreotide (60mg)

every 28 days.

The study included 229 patients, and the primary

endpoint, mPFS, was achieved, with an impressive 80% reduction in risk

of disease progression in the Lutathera arm (HR 0.20 IC 95% 0.130.34).

This result translated into an mPFS not achieved yet in the Lutathera

arm, and a mPFS of 8.4 months in the Octreotide arm (60mg every 28

days). The added value of the study is that it is the first clinical

trial to show favorable results of the use of Lu 177, in a randomized

comparative trial.

Another trial, TELESTAR [4],

studied the role of TELOTRISTAT ETIPRATE, which acts by inhibiting

tryptophan hydroxylase, the rate limiting enzyme in the conversion of

tryptophan to serotonin. The primary endpoint of the study was to reduce

symptoms associated with carcinoid syndrome such as diARGHhea in

patients on octreotide (30mg every 28 days) whose symptoms persisted.

The study included 135 patients, randomized to three

arms; in two arms two different doses of the drug were tested, and the

other arm was given placebo (in fact, these patients were on

Octreotide). In both arms treated with Telotristat a 40% symptom

reduction was observed, and the responses was sustained in time. Also,

there was a reduction in the levels of 5HIAA, as a specific marker of

carcinoid syndrome. This opens the door to a new oral treatment option

for functional tumors, with carcinoid syndrome previously managed with

standard doses of Octreotide.

The data in CLARINET [5]

have been updated; the open phase was presented, that is, the

assessment study in terms of efficacy and safety in patients originally

randomized to lanreotide vs placebo in the CLARINET core study. The open

phase included patients with at least stable disease in the original

study after 2 years of treatment, and patients who had received placebo

during theinitialrandomization and evidenced disease progression.

A total of 88 patients were included, 41 previously

treated with lanreotide and 47 in the placebo arm. Thirty nine percent

of the patients included had intestinal tumors, 38% had pancreatic

tumors, and 23 % had tumors in other locations or of unknown origin. As

for safety, patients who continued on active treatment reported less

adverse effects during this open phase of the study as compared to the

initial phase. The group of patients treated with lanreotide, who were

previously included in the placebo arm, evidenced a higher incidence of

diARGHhea during the initial phase; however, no other adverse events

were observed. The median PFS in the CLARINET core study was 32.8

months.

The median PFS in the open phase in the group who had

not received active treatment before (placebo arm) was 14 months. The

results show the antiproliferative effect and the safety profile of

prolonged treatment in patients with intestinal and pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumors, G1-G2 with a Ki as high as 10% with Lanreotide

(120mg every 28 days).

Update on the Treatment Guidelines of NETs, ENETS

(European Society of Neuroendocrine Tumors). New treatment guidelines

for neuroendocrine tumors of gastroenteropancreatic origin have been

published this year. It should be underlined that these Guidelines are

the result of the Consensus Meeting held by the members of the Advisory

Board in Europe, the United States and Latin America (Argentina and

Brazil). Different topics such as location of the primary tumor and

disease stage are discussed at the Consensus sessions. Also, treatment

options and algorithms in liver metastatic disease and high-grade

neuroendocrine tumors are also dealt with.

In the case of neuroendocrine tumors of intestinal, jejunum- ileum [6]

origin, the role of surgery as a curative procedure is underlined, or

the role a large dissection of the mesenteric lymph nodes as a

palliative procedure.

The management of superior mesenteric artery

involvement should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team, although

resection is not always feasible in advanced disease. In terms of

overall survival (OS), the role or potential benefits of surgery for

primary tumors of intestinal origin in asymptomatic patients with liver

metastases is still debatable. The European Society is conducting a

comparative clinical trial in order to find an answer [7].

A cholecystectomy may be performed during surgery to

avoid the risk of complications due to bile duct lithiasis, another

topic without clear supporting evidence, but with the consensus of the

participants. Another important point underscored in the new version of

the Guidelines is prophylaxis against carcinoid crisis with the use of

somatostatin analogs in patients with carcinoid syndrome. The design of

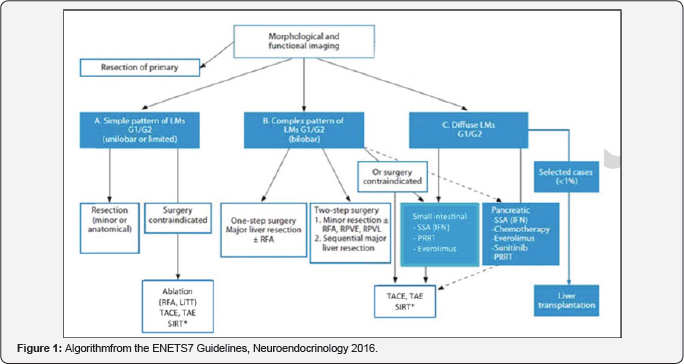

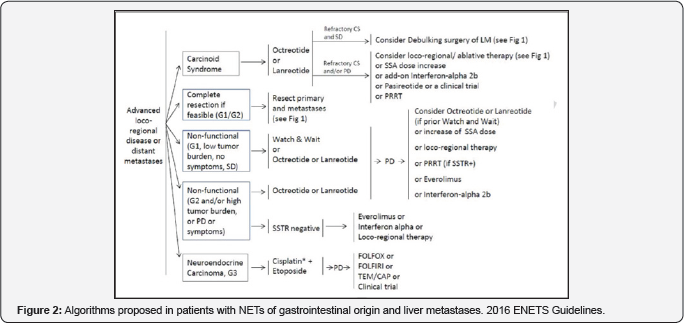

Treatment Guidelines and an Algorithm for patients with neuroendocrine

tumors and liver metastases has been very important, for it is the most

common location for this type of tumors (Figure 1 & 2).

One of the important aspects to underline is the

staging system suggested by ENETS, in relation to 3 subtypes of liver

involvement. In the case of a single pattern, in G1, G2, that is

unilobar or restricted involvement, surgery plays a key role. In the

complex or bilobar type, surgery is the option in some cases, as well as

the liver regional management such as liver embolization of

chemoembolization. Finally, the diffuse type is the most common clinical

scenario, and is the ideal subgroup for different systemic treatment

options or regional liver management, so that surgery is ruled out for

this subset of patients. This subdivision may be easy in the theoretical

setting but in clinical practice it is not so easy to stage patients in

these three categories. Our Group is currently working on a registry of

patients with liver metastases to estimate the frequency of

presentation, in which cases surgery is performed up front, which are

the treatment lines used, according to the preferences of the attending

physicians, etc., in a series of cases in Argentina. Finally, the update

on the treatment Guidelines also includes algorithms for neuroendocrine

tumors with liver metastases, considering some differences between

tumors of gastrointestinal and pancreatic origin.

In the algorithm we should underline four or five

practical questions to be answered in order to define the initial

treatment.First, if the patient presents carcinoid syndrome, i.e. a

functional or non functional tumor; second, is surgery as a curative

procedure an option?; third, if the patient has a functional tumor, and

it is a G1, with a low volume of disease and is asymptomatic; fourth,

the same case as before but with a larger volume of disease and

symptomatic or with progression of disease, the possibility of target

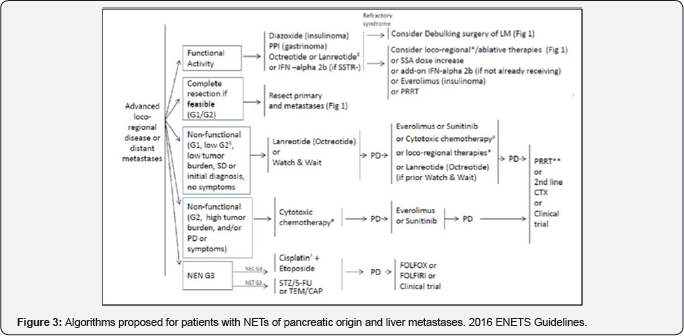

therapy, such as everolimus. Finally, does the patient have a G3 tumor?

In this stetting, the only option isplatinum-based chemotherapy (Figure 3).

Legend : PD progressive disease, SD stable disease,

SSTR somatostatin receptor, SSA somatostatin analogs, CS carcinoid

syndrome, PRRT peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, LM liver

metastases, TEM/CAP temozolomide/capecitabine, STZ streptozotocin, 5-FU

5-fluorouracil. Similarly, for NETs of pancreatic origin treatment

decisions are based on the same questions presented for (Figure 2) in reference to NETs of gastrointestinal origin.

The subdivision of G3 tumors into G3 NETs, well

differentiated tumors, and G3 NECs, poorly differentiated tumors with

only one treatment option based on platinum- etoposide chemotherapy

should be noted. Furthermore, we should underline that observation is

less feasible in pancreatic tumors, that is, no active treatment in the

setting of advanced disease after the new evidence available from the

CLARINET trial, which included gastrointestinal and pancreatic tumors

with a Ki as high as 10%. Also, there may be a more importantrole for

chemotherapy although with poor levels of evidence to define the best

chemotherapy scheme in this context.

Conclusion

Interesting development is ongoing in the field of

neuroendocrine tumors by cooperative groups and well designed clinical

trials to answer questions about systemic, surgical or local liver

ablative management. Working groups like NANETS, the American Group, or

ENETS, the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society, have pioneered the

development of both diagnosis and treatment guidelines for this

condition. ARGENTUM, the working group in our country, more humbly and

with certain limitations, studies the local data and provides a chance

for sharing experiences between our region (LATAM) with the leading

centers in the world. Our great challenge for the future is to learn

more about the best treatment sequence for this condition as well as the

molecular characterization of different tumor subtypes, in order to

optimize resources and take a step closer to precision medicine or

personalized medicine in this field. A multidisciplinary approach

together with the integration of the participating specialists, not only

oncologists and surgeons, is the key to succeed and advance in research

to offer patients with this condition the best treatment option.

To Know More About Advanced Research in Gastroenterology &

Hepatology Journal

click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/argh/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/argh/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment